Trio of Pebble Watches, funded with a very successful Kickstarter. Photo courtesy of Pebble Technology, CC BY-SA 1.0.

Most people have probably heard of crowdfunding by now—the practice of funding a project by collecting small amounts of money from a large number of people, usually via the Internet. Sites such as ArtistShare (launched in 2003), Indiegogo (founded in 2008), Kickstarter (founded in 2009), and Gofundme (founded in 2010) receive a lot of traffic and have generated millions of dollars for successful campaigns. These sites work on a donation-based model, where contributors donate funds to support a creative project or a charitable cause, often in exchange for rewards. However, crowdfunding platforms are appearing in many niches, such as those that specialize in funding scientific research or local development projects, and there is increasing interest in crowdfunding sites that use an investment model rather than a donation model.

One form of investment crowdfunding that has been around for almost a decade now is peer-to-peer (P2P) lending. In 2005, Zopa launched in the United Kingdom, and they are still the largest company in the U.K. P2P lending market, having facilitated £712 million of loans. In the United States, Prosper was first to the P2P lending market, launching in February 2006. By the end of that year, they had 100,000 members and had facilitated $20 million in loans, but now have over 2 million members and have facilitated $2 billion in loans. Lending Club followed, launching in May 2007 as a Facebook application, but offering a standalone website competing directly against Prosper soon after. They are now the largest P2P lending site in the U.S., having facilitated more than $6.2 billion in loans as of September 30, 2014.

As crowdfunding sites using investment models have grown, so too have efforts to regulate them. In 2008, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) required P2P lending companies to register their offerings as securities in conformance with the Securities Act of 1933. Prosper and Lending Club temporarily had to suspend offering new loans while completing the expensive and time-consuming registration process. However, both companies gained SEC approval to offer investors notes backed by loan payments, and both formed partnerships with FOLIOfn, Inc. to create a secondary market for their notes, thereby providing investors with liquidity that had previously been missing from the P2P lending industry.

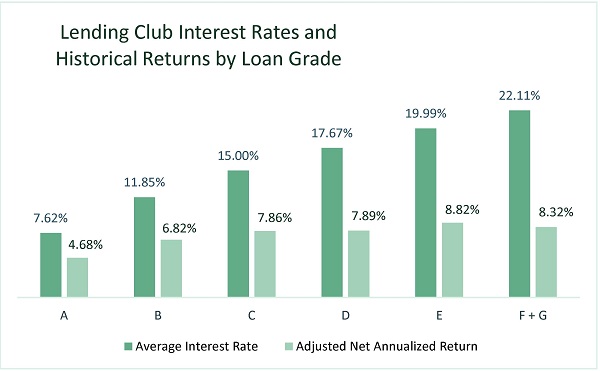

Chart by Greenfield Advisors based on January 14, 2015 data from Lending Club.

Recognizing that more needed to be done to boost the struggling economy, the Obama Administration hosted a conference in March 2011 titled “Access to Capital: Fostering Growth and Innovation for Small Companies.” The ideas developed at the conference led to the Jumpstart Our Business Startups (JOBS) Act, passed by Congress with bipartisan support and signed by President Obama in April 2012. The JOBS Act of 2012 updated some provisions of the Securities Act of 1933, and two parts of the act are particularly relevant to crowdfunding.

Title II of the JOBS Act, which took effect September 23, 2013, eliminated the prohibition of general solicitation and general advertising in Rule 506 and Rule 144A offerings, thus allowing companies to publicly advertise their attempts to raise capital, thereby paving the way for a new crowdfunding model—equity crowdfunding. Equity crowdfunding allows people to invest in a company that is not yet listed on a stock market in exchange for shares in that company rather than interest or rewards as in the previous crowdfunding models. Shareholders have partial ownership of the company they have invested in and stand to profit if that company does well, although they also risk losing some or all of their investment if that company, or perhaps the facilitating company, fails. Sites such as EquityNet (founded in 2005) and Fundable (founded in 2012) were some of the first sites in the U.S. to take advantage of this new crowdfunding model once the new SEC rules took effect, while equity crowdfunding sites such as Crowdcube (founded in 2011) and Seedrs (founded in 2012) were undergoing a similar process in the U.K.

Despite the fact that crowdfunding was supposed to democratize finance, currently most investment crowdfunding in the United States is restricted to accredited investors, those who have income of more than $200,000 per year or a net worth exceeding $1 million, excluding the value of their primary residence. Title III of the JOBS Act was supposed to allow nonaccredited individuals to participate in equity crowdfunding, investing up to 5% of their annual incomes or $2,000, whichever is higher, but the SEC has repeatedly delayed issuing the regulations necessary for Title III to be implemented. Most recently, SEC Chair Mary Jo White has announced that there is no “drop dead date” for issuance of a final rule, although the SEC had previously indicated that their target date for the rule had been delayed until October 2015, which means implementation would be unlikely to occur until sometime in 2016.

Meanwhile, the industry continues to grow and evolve. According to Chris Tyrrell, chair of advocacy group Crowdfund Intermediary Regulatory Advocates, “In the first seven months of operation, over $100 billion in private offerings used some part of Title II.” Several U.S. states have already enacted or are considering enacting crowdfunding exemption laws to facilitate intrastate investment offerings, which are already exempt from SEC regulation. And on December 11, 2014, Lending Club had an incredibly successful initial public offering (IPO), raising $870 million and speculations that other crowdfunding sites may also opt to go public.

While we don’t see crowdfunding replacing traditional financial institutions or angel investors, it looks like it will continue to be a viable alternative, and having additional options for funding can only be a good thing.

If you’ve used one of these crowdfunding sites, feel free to share about your experience in the comments below. And watch for a subsequent post, where we’ll discuss how crowdfunding is being used in the real estate industry.

Recent Comments